Outsider Market: Recoding of Schizophrenic Desire

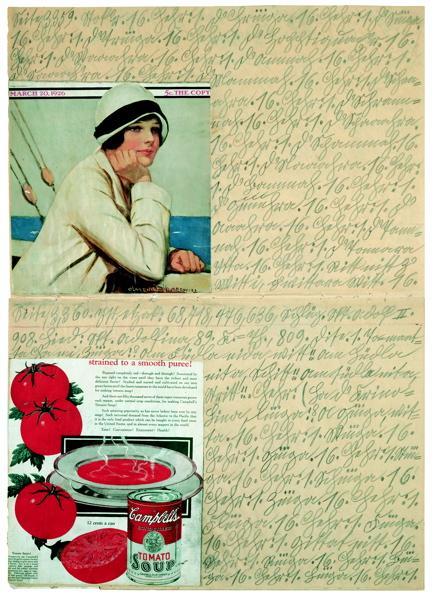

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s soup cans, 1962, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 32 canvases of 51 x 41 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA.

Since its appearance, Art Brut has always been a controversial term that was primarily circulating in France. British art critic Roger Cardinal used the term Outsider Art in attempting to translate the French term l’Art Brut, which literally means raw art, into English in 1972. In the 1980s, a specific art market focusing on the kind of controversial creation in question emerged in Western Europe and North America and expanded to the other economically developed regions of the world over a span of decades. This niche market, whose operational logic is the same as that of the mainstream art market where private as well as public actors influence the perception of the works, is called Outsider Art market and has brought about the popularization of the kind of controversial creation in question. Yet, although l’Art Brut (raw art) was referring to extremely subjective expressions of intense sensibilities of the outsiders, its English translation as “Outsider Art” is generally understood as creative works of outsiders. This simplistic understanding of the kind of creation in question caused conceptual problems of its own because “outside” is not an ontological place whose borders can be set once and for all, and hence being an outsider is too controversial a subject to become a defining characteristic of anything. This elusive notion is especially difficult to grasp by insider categories. Yet many launched into the difficult task of defining the authentic outsider. For some, the outsiders of the Outsider Art were those who had no formal art education. For others, they were those who withdrew from society. Almost each category was controversial. Were not withdrawals from society actually marginalized and left outside? Almost each category was bringing in controversial subcategories, such as withdrawals or marginalized people, because of mental disorder, physical disorder, poverty, perversion, and so forth, each category and subcategory denying authenticity to another. Hybrid categories, such as creators who did not have a formal art education but were actively participating in the art world or those who had an art education yet withdrew from society were specifically confusing for all. The need to categorize and set categories hierarchically had so captured the thoughts of some that they created a spectrum of outsiderness to determine who were the most radical outsiders to call their production the most authentic Art Brut/Outsider Art. In addition to creating a vast controversial literature, such attempts to understand the outsider with insider categories contributed to the mystification and even romanticization of the outsiders.

Within the Outsider Art market, Art Brut/Outsider Art works were valued on the basis of mentalist arguments that could be neither falsified nor verified, such as the claim that Art Brut/Outsider Art creators did not care about the social or financial value of their works and so did not want to share their works with society. Later on, when some of the creators in question showed interest in sharing their work with the public for some reason, their works were discredited because their creator lost the status of an authentic outsider. Even Dubuffet excluded certain works like those of Gaston Chaissac from his Art Brut collection because the creator got too heavily involved in artistic circles, says Peiry. According to Dubuffet, the distance of the creator from culture, and, accordingly, from the art world, was an important criterion for the authenticity of an Art Brut work. As a consequence of their distance from culture, it is expected that Art Brut creators are not concerned about the social and financial outcomes of their creations, as are professional artists. Thus, the art world seems to agree on the idea that it is not to the Art Brut creators or the outsiders, to bring their creations into the art scene but to the insiders who valued these creations according to their own frameworks that are certainly conditioned by culture and art culture. Yet, in addition to the self-conflicting claims on authenticity and on the cultural authority to define the authenticity, the criteria applied to measure the distance of the creator from culture are arbitrary in the sense that they do not suggest more than a fallacy of defective induction based on overgeneralizations, oversimplifications and mind reading. .

Adolf Wölfli, 1929, Untitled known as Campbell’s tomato soup, P.3359 from Funereal March, collage on newspaper, 70 x 50 cm, Adolf Wölfli Foundation, Bern, Switzerland

Thus, the definitions of Outsider Art proliferated almost arbitrarily to the extent that Roger Cardinal himself, decades after his translation, was overwhelmed by its prolific and controversial definitions and stated that if everything was to be considered as Outsider Art, the term would come to be devoid of all meaning, according to Cardinal. Accordingly, Outsider Art has become an umbrella term, covering a wide spectrum of art forms, and is accused of being a commercialized form of Art Brut, undermining its artistic integrity for the sake of market expansion.

The Outsider Art market, as an extension of the art market, certainly commercializes the kind of creation in question and undermines its authenticity. Yet one can argue that it does so positively because what it undermines is nothing but an already problematic discourse on authenticity. The extension of the meaning of Art Brut, owing to the manifold definitions emerging within the Outsider Art market, is a consequence of the de-codification process of capitalism that undermines the established values, meanings, codes that interrupt or slow down the flow the capital. Marx and Engels had long ago celebrated the decodification of old values in capitalism as liberating. One of the most prominent examples of capitalistic liberation from the art field is perhaps the Pop Art movement. In the 1960s, the Pop Art movement pointed to the artistic character of everything from daily objects to commercial products. By doing so, it was undermining the hegemonic discourse on authentic art that problematically claims its authority to define and detect valuable works of art and was democratizing and liberating artistic creation and appreciation. On the other hand, similar to Cardinal’s concern in regard to Outsider Art, Baudrillard had criticized the Pop Art movement, arguing that if everything became art, art would not mean anything and would simply disappear. He pointed out that the decodification process of the market was far from being purely liberating because capitalism was decodifying old meanings only in order to recodify them in terms of capital. As did Baudrillard, Deleuze and Guattari too argue that the market decodes all, especially what interrupts or slows down the flow of the capital, only to recode all in terms of money. Together with the solidified essential identities, the possible perceptions of the world that unsettle capital are decoded and recoded in terms of capital. Expectedly, the notion of outside cannot escape from this de/recodification to be brought into the market. Consequently, the Outsider Art market is even more paradoxical than an outsider art as addressed in Bourdieu’s critique. So, on the one hand, owing to the prolific definitions, the market undermines fairly the problematic claim on authenticity of the schizophrenic object, whereas, on the other hand, it reduces the schizophrenic object into a market category and recodes the free desiring-production of the schizophrenic which unsettles the mechanisms of the capitalistic coding of desire, as market goods. It causes mystification and romanticization of outsiders for the sake of market profit and overshadows the sociopolitical character of Art Brut as a schizophrenic object of schizophrenic desiring-production that unsettles the profit-oriented capitalist logic.

.